👋 Hi! Tell us about yourself and your training

Hi! My name is Jonathan, I am 34 years old and was born in Montréal, Canada. I’ve been training numerous disciplines for a long time, starting with gymnastics at age nine. My parents had first sent me to gymnastics at age six because I had “too much energy”. For whatever reason, I was put in an all-female club and I quit soon after a coach told me I had no future in gymnastics.

A few years later, I joined my elementary school’s circus program. My grandparents surprised me with tickets to Quidam, a Cirque du Soleil classic, and I was blown away by the physical abilities of the acrobats, especially during the Banquine act. I then asked my parents to put me back in gymnastics, but this time, in a club that trained male athletes.

We visited a few clubs and all of them were very friendly, but finally landed on IMCO (now Centre Sablon), in Montréal. I saw a group of senior athletes training and they looked so impressive and strong that they seemed like characters out of Dragon Ball, which is one of the most motivational comics to ever influence the fitness community.

In short, that’s where I wanted to train. The idea of high-level gymnastics scared me to death, but I wanted to become superhuman just like the elite gymnasts that I had just seen.

The club was far from where I lived, but my parents were willing to go above and beyond so that I could train the way I wanted to. For the first month or so, I trained three times per week, with each session lasting for three hours. Even my coach looked super strong (I later learned that he was an Olympic hopeful and was Philippe Chartrand’s training mate). I did well enough that I was transferred to a group that trained four times per week instead of three.

Training gymnastics was quite difficult. Learning new movements was often scary, and initially, gymnastics conditioning left me out of breath and nauseous. During my first two or three years of training, there were some difficult conditioning sessions that I was unable to complete. The training was very strict. But it was my choice to do it and I was getting better and stronger, as a result. Over time, I became very self-disciplined and refused to take any days off from training. One year, my coach even threatened to kick me out of the club if I came back to train during our two-week summer vacation.

When I was 12, I injured my heels and Achilles tendons pretty badly. I didn’t know the extent of the injuries at the time and did my best to keep training, anyway. The pain was quite extreme, and as time went by, training became progressively more difficult. Two years later, my injuries were investigated further, and it was discovered that my heels were shattered, and my Achilles tendons were holding on by a thread. My doctor didn’t know whether I’d make a full recovery. I was unable to do much leg training the following year, but I still attended training every day. Since I couldn’t do much and had to wear a special boot (I only had one, so I had to heal one foot at a time,) I started doing my conditioning earlier than the other guys. Because I was bored, I would repeat the conditioning two or three times, and after a while, I started adding to it by inventing new exercises and figuring out how to program my own training.

After a year of recovery, I was able to start training normally again. I still had to be careful with my ankles for a few more years, but in the end, I made a full recovery. Because of the experience, I found myself with an increased work capacity and could handle more physical training, which I took advantage of by doing some extra conditioning on my own. By age 16, I had caught up enough that I was able to partake in national competitions. By age 20, I was still climbing the ranks, finishing with second place overall at the Canadian national championships (open category level 6).

Most high-level gymnasts face increasing pressure to eventually do something else with their life, especially when it becomes clear that they won’t make it to the Olympics, and I was no exception. My family had sacrificed a lot for me to be able to train the way that I did. My coaches had put a lot of effort into my training and my club had helped me continue training with financial aid.

The governments of Canada and Quebec had given me bursaries when I placed well in competitions, which helped me to keep training. I owe a lot to a lot of people. Nonetheless, it was not viable in the long run. I didn’t want to stop gymnastics and wanted to keep training and improving, but I also had to figure out what I was going to do in the future.

I had gone to college for two years (one in electric engineering and one in human sciences) but left because I didn’t want to incur any student debt, especially given that I didn’t necessarily want to work those fields. Eventually, with mounting pressures, I did a one-year professional firefighting program at IPIQ. But I didn’t necessarily want to be a firefighter, either.

I had many interests, such as writing, computer programming, computer hacking, but above all, I had a thirst for adventure. I didn’t know what I wanted to do, and I didn’t know what my path would be. But I never felt like I was meant to be sedentary and didn’t want to settle for anything.

After receiving my firefighting diploma, I was approached by some people who said they worked with the US government for a research program on martial arts training techniques. That program included some very unusual training elements such as “pain control” and I was intrigued enough that I volunteered myself as a guinea pig in order to learn what I couldn’t learn elsewhere. I also started training parkour a lot, with an emphasis on the “operational” aspect of it, (accessing hard to access places and becoming really good at escaping).

On the side, I worked at a public library. I also made a few friends, with whom I built a secret training camp in a wooden area. So, when I wasn’t doing parkour or testing very gruesome training techniques, I spent my days training with my friends at our secret camp.

After over a year of that, I decided to leave the Montréal area. All in all, I had $1000 CAD, a big backpack full of survival tools and food, and one travel buddy. My mom made me promise that I’d only leave for one year, and I did, even though I knew that there was almost no way I’d be back within a year.

First, I headed to Eastern Québec, where there was someone I really wanted to train with. Then I went to Toronto, then to New York City, and then back to Toronto. Then, I slowly made my way to Vancouver, stopping in most major Canadian cities to train with different people in different environments. I lived outside almost the entire time, sleeping on rooftops in most cities, or hiding in forests in rural areas.

As winter was approaching, I arrived in Vancouver. I had been travelling and living outside for half a year and had $50 left. My intention was to find some work and stay until the spring. At first, I spent some time getting to know my surroundings and gathering information about possible jobs and homeless services in Vancouver.

I initially wanted to borrow a friend’s bicycle and be a bike courier, but I needed to get a permit, and the city only gave permits to fancy people who have an address. Two weeks after my arrival, two more of my friends from Québec made their way to Vancouver. During that time, we lived in homeless shelters and tried to find work. A couple times a week, we would get paid to pick syringes off the street for a few hours, and I started busking, doing gymnastics and strength tricks on Granville street to earn money.

At first, I wanted to go back to living outside and my idea was to build a teepee in the woods and busk and find odd jobs until I had enough money saved to keep travelling. But one of my friends who joined, a brave 17-year-old, wanted to have an address so that he could find legitimate employment and go meet his dad for the first time (he made it).

The day before Halloween, something pivotal happened as I was performing on the street. It was a cold, rainy day, and I was exhausted. I had been performing for over an hour and a half, and I was just about done, when I saw a really pretty girl walk towards me like she wanted to talk to me.

She asked me if I had a job and if I had a home, to which I replied in the negative. She then told me that she worked for a local circus and that they had just lost their top acrobats and based on what she saw, she thought that she could get me a job. As you can imagine, that made me very happy. I took down the company’s email address and phone number, (as well as hers!), and as soon as I was done busking, I sent them a message.

On November 1st, my friends and I moved into a small apartment in a seedy part of town. A day or two later, the owner of the circus messaged me back and I visited his circus school. When I got there, everyone wanted to test me, and they kept asking me to try all kinds of stuff.

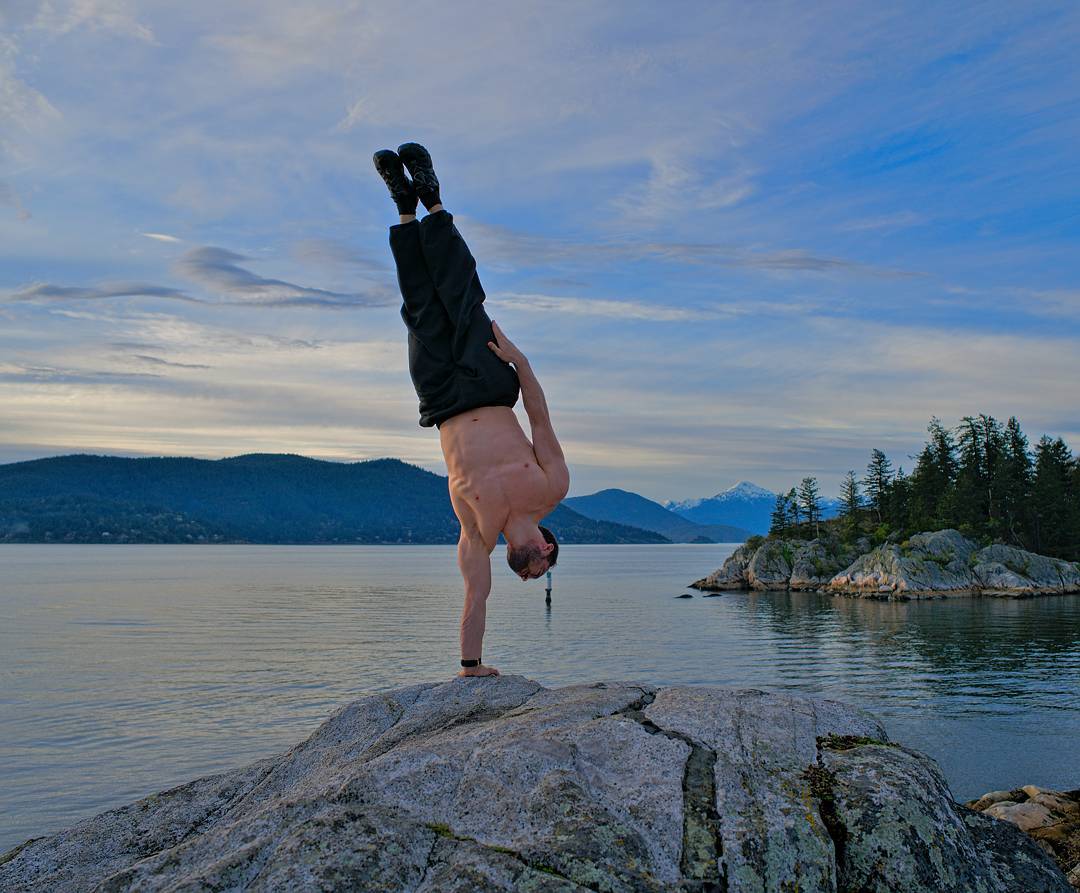

The head coach seemed impressed and said that with my shoulders, I could do almost anything I wanted. They asked me what I wanted to do as my main discipline. Without much hesitation, I answered “hand balancing!”, which made a lot of sense given that handstand push-ups were too easy and that I was hoping it would be possible to learn a one arm handstand push-up.

Also, hand balancing seemed like a wise choice for someone who just wants to go around the world and train on the cheap. If I became a good enough hand balancer, and became strong enough, I could go just about anywhere and perform on the street, coach people, or find other means of work.

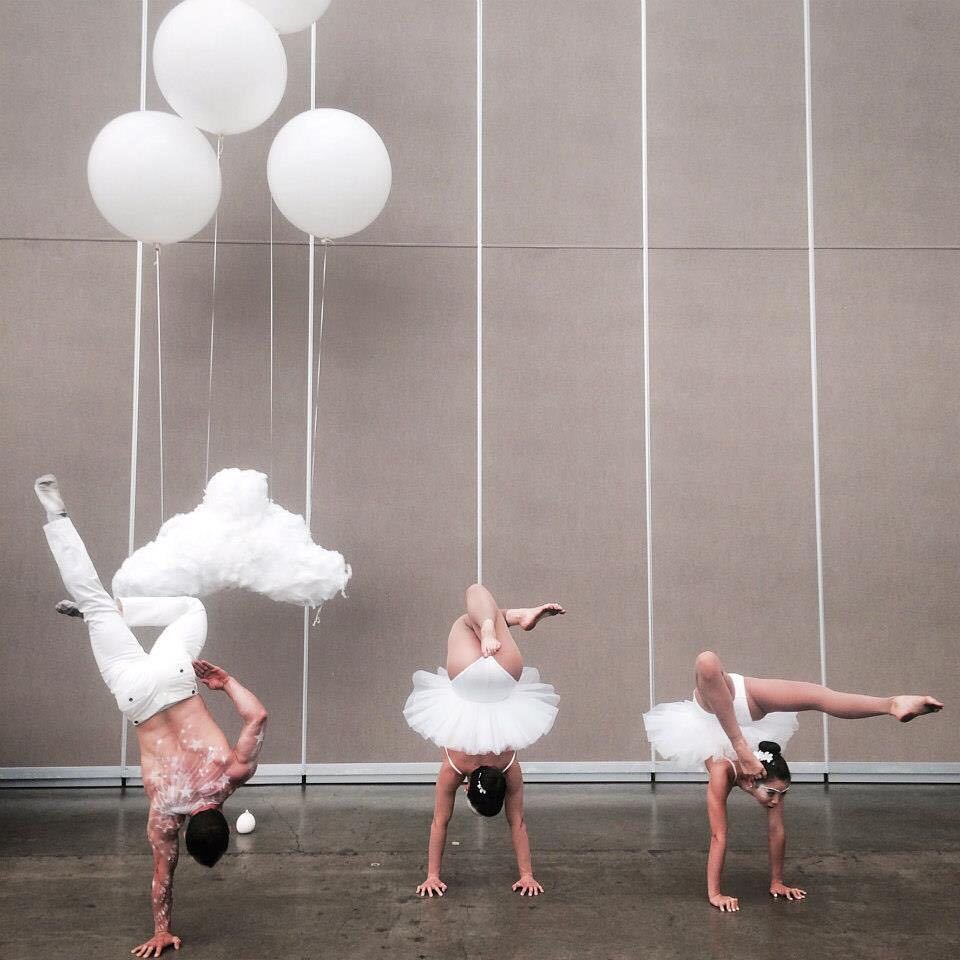

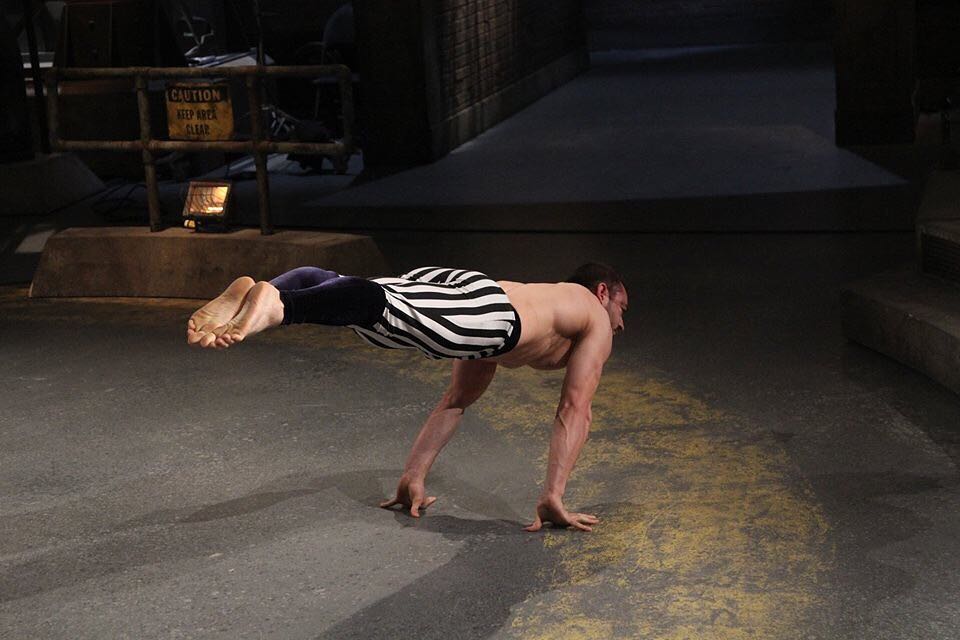

The owner of the circus told me that if I did well, they would have me perform. Less than a week later, they brought me in for my first gig, where I had to go around a bit and do a sequence here and there. Fortunately, I did really well. From then on, they tried to give me a few gigs a month to help me survive while I spent time learning. They assigned me to train with a Cuban man, who used to be a hand balancer.

For a few months, he helped me figure out the basics of a one arm handstand. Though, he often told me that I should’ve chosen something easier because there was no way I would be a worthwhile hand balancer early enough not to starve.

He was right. Every weekday, I went to the circus school and trained. On evenings and weekends, I did parkour outside. I made around $300/month at that time, just barely enough to survive. The head coach knew that if I wasn’t outside trying to find food or money, I wouldn’t have anything to eat, so he brought me a lunch bag, every day.

Becoming a hand balancer was taking a lot longer than I had anticipated, and I had not foreseen how much of a rabbit hole hand balancing is. I then realized that I was going to stay in Vancouver for longer than I had anticipated.

Over the next half year, more and more people came to live in our apartment, which made our rent extremely cheap. At its cheapest, we paid $80 each per month, and those who were unable to pay went around looking for food to bring back home and share with the rest of us.

Many volunteered to cook for the homeless in a mission’s kitchen, and for that, we received food regularly. Those circumstances allowed me to be able to focus on training, despite being extremely poor. But all good things eventually come to an end. My friends and roommates eventually all had to move on with their lives, and by summertime, everyone else was gone and I needed to find a new home.

I looked around, but the places I visited that I could afford were either horrible or were not intended for me. I remember one place that I could afford (barely) reeked of human decay. I was willing to live in bad conditions, no problem, but people were clearly dying in there, and the one thing that I could not afford was to get sick.

I really didn’t want to have to share a space with people who kept dying. A parkour friend saw that I was in need, and he happened to own a small gym. He told me that I could come and live in the gym, which I accepted instantly.

Over the next year, I didn’t go to the circus school as much since I lived in a gym, but I kept in touch for shows. I also started building a clientele, coaching people for gymnastics strength and general fitness. My prices were very affordable. Just enough for me to be able to pay my part of the rent and food. With that, I never again needed to steal food or warm clothes to survive.

Soon, the gym owner was going to open a bigger gym, which we couldn’t live in, so I had to figure out what to do next. I didn’t have enough money saved to hit the road again, but I knew it was just a matter of time. I was asked by the circus school to coach a professional development program, which I agreed to, so I could save up and resume my travels.

When I started coaching, I quickly realized that the students lacked a lot in terms of strength and conditioning and that their handstand training hadn’t been very methodical. So, I spent time figuring out some better ways to train them and they became less weak fairly quickly. Nonetheless, I still intended to leave by the end of that year. I wanted to head South, go down the West Coast of the US, cross Central America, and make my way to South America by land, through the Darién gap.

Upon hearing that, the pretty girl who had found me on the street got really upset, realizing that she had feelings for me that ran deeper than friendship and we started seeing each other. Thinking that it would be nice to have a girlfriend, and having enough work to make a living, I decided to stay longer. Over time, hand balancing became more time consuming to the point where I didn’t have time to do parkour anymore.

I felt that, as a hand balancer, I really needed to get better. Hand balancing, in itself, presented a ridiculously hard challenge and I just couldn’t give up. I also felt that I had to keep improving for my students’ sake. If they got better than me, who could they learn from? There was no one in the region who was at a high skill level, so I had to do it. And, it was clear to me that I only really had a place in Vancouver because I was filling a gap. There was no one better than me around British-Columbia at that point in time, and I was worried someone better and more knowledgeable could come and take my place. I knew I wasn’t at the top because I was good—I was at the top because there was no one else and that’s no dignified way to victory. At any point, if someone better suited to teach my students had shown up, I was ready to concede my position and leave.

In the end, it didn’t happen, and I stayed in Vancouver for nine years. Both for my students and for my girlfriend. I managed to contain my thirst for adventure, quenching it with occasional trips for performing, touring, or social circus. It wasn’t easy, though. Many times, I thought of leaving everything behind again, and just starting anew. I love the idea of arriving somewhere new with only the bare essentials for survival and figuring a way to build up from there again. Even now, well in my thirties, the idea is appealing to me. But I didn’t, because I am also very loyal.

As I got older and acted more responsibly, I also longed for more training time—ultimate training, with no barriers to how much I can practice except for my physical limits. And I still wanted to become a more seasoned performer, for my students’ sake. I had performed quite a bit, yes. But I wasn’t a seasoned performer, and due to my lack of experience, I suspected that I would keep falling short with helping my students in that regard.

In the meantime, my girlfriend decided to go back to school, which meant she would temporarily move back home, and the program I was teaching had transformed quite a bit to where I felt I could make an exit. Many of them became successful performers, with several moving to Montréal.

So, I decided that by the end of the summer, I would move back to Montréal to train full-time. Living in Montréal costs a lot less than living in Vancouver, the apartments are bigger, and there are more employment opportunities for performers over there. Montréal was the place to be for circus artists.

The night I arrived in Montréal I couldn’t sleep. I laid on the floor all night in one of my old students’ apartment, wondering if I would be able to go back to my girlfriend if I failed to become a world class hand balancer and didn’t find work before my savings ran out. I spent the next month looking for a place of my own that would be big enough to build a home gym. Fortunately, I did, and I moved in at the end of August. After a few restless days, my gym was ready, and I started training.

I love training and am a lone wolf, by nature, but I hadn’t realized that isolating myself and training nine or ten hours a day would be difficult. (Surprise, it was!) It took several months for me to get used to it and forget the feeling of being a prisoner. But in the end, that doesn’t matter. I’m here to get better and stronger, which I have been doing. The least I could do was to show up in a good enough shape for others to want to train with me as a peer. After a year and a half of isolation, I finally started going outside and visiting other training spaces to meet other hand balancers and circus artists.

I soon then got lucky again as someone at a circus space saw me training and asked me if I wanted to join his company for a short tour in Germany. I hesitated a bit because it conflicted with other plans I had and initially I refused, but deep down, I really wanted to do it. So, I called back, apologized for initially declining, and agreed to go. But then, SARS-COV2 started infecting the world. The tour was postponed, and for now, I am back in my training dungeon. More time for me to get stronger and better. I hope you are also making lemonade out of lemons.

Here’s my advice to you: If you want something, stop messing around and start putting in the work. You can learn a lot through personal experimentation. Do not be scared of overtraining and do not try to optimize everything to the smallest detail before you get going. Just get going. Do all the good quality work that you can recover from, at that moment. Don’t be scared of discomfort, either. Learn about yourself. Learn about your physical and mental limitations and find ways to overcome them. There are no secrets, no shortcuts, so don’t waste your time looking for them. Mental resilience, patience, and consistency beat everything else. I don’t know what your goals are, but if you want it badly enough, go balls out for it.

⏱ Describe a typical day of training

A well-trained person learns everything quicker and can go on a mission and come back successful.

A typical day of training for me is pretty simple: I wake up, eat breakfast, and start warming up. Then I do handstands for many hours, followed by some strength training, and if I have time (I never do), I stretch. Finally, I eat a big dinner, read a bit, and then go to bed. I tend to start training at around 11am or 12pm and finish at 9 or 10pm.

The content of my training changes a bit from day to day. I tend to use splits loosely based on movement patterns rather than muscle groups. I am not a bodybuilder, so I practice movements I want to become good at because they push my body and mind to adapt in a manner that I think is desirable, (meaning, advantageous to me in terms of performance).

I don’t want people to focus too much on my personal training program, because it’s not how I do my splits that matter. Rather, almost any program can work for people as long as it makes sense to them; is appropriate for what they want to achieve; and allows them to practice exercises with good intensity, frequency, and volume. As long as those criteria are met, people should improve, provided they have enough time, eat enough, sleep enough, and don’t lead too stressful lives.

To come back to my own training, it evolved over the years. As a gymnast, my training was about being good at gymnastics, and the goal of gymnastics was to win gymnastics competitions. After that, I wanted my training to be more generalized. The idea was that no matter what I encountered I would be prepared.

So, I trained hard to be able to adapt to anything. A well-trained person learns everything quicker and can go on a mission and come back successful. Hand balancing became my mission. So, I would say, these last eight years or so were quite focused on hand balancing. The catch is that hand balancing can be an infinite mission, so I make sure to keep doing lots of general training alongside it.

👊 How do you keep going and push harder?

Well, it’s pretty simple. Either you truly want to achieve something, or you don’t. If you want to achieve it, you will put in the work. We all have occasional days when we choose to rest, that’s fine.

Taking time to rest is not an issue but staying the course is what matters in the long run. Stay focused and prioritise wisely. If training isn’t an important priority for you, don’t expect to get the same results as someone who has dedicated their life to it.

Don’t waste your time lamenting what you haven’t worked for. If you want it as bad as you think you do, put in the work. If not, admit that you don’t want it as bad as you thought, or accept that you, and you alone, are responsible for your lack of achievement. You reap what you sow.

With that said, an important topic of discussion is habit formation. Make sure your training is sustainable and progressive. Adhere to it strictly for the first month and it will become easier. The longer you stick to it, the more natural it will feel to keep going, and the easier it will be to start again after taking a break.

Also, it’s important to note that whenever you do something new or different, it can take a couple of weeks to adapt to it, and during that adaptation time, you will feel very beat up.

Don’t give into feelings of apprehension or defeat, your body will get used to it. But also, use your experience and common sense to avoid doing things that will clearly lead to injury.

🏆 How are you doing today and what does the future look like?

I am doing pretty well these days. A month ago, I achieved a personal record and did alternating one arm handstands for 12 minutes. Ideally, I wanted to get a clean 10 minutes, with legs together the whole time. So, I’m aiming for a 15-minute personal record, and hopefully the 10 minutes will become easy enough that I can do it cleanly.

After that, in terms of endurance, I will probably keep aiming higher little by little. I also really want to improve my one arm press, which I have done on and off, but never cleanly enough. And, I want to become able to do at least five reps on each arm.

I’m also recovering from a partial bicep tear that occurred while I was doing a weighted planche. In the near future, I want to get back to the planche level I was at previously, and then push forward until I can hold it cleanly for 30 seconds.

In terms of strength training, my long-term goal is still the one arm handstand push-up. But right now, I’m focusing on gaining general strength, and I am not going to focus on the one arm handstand push-up until I can military press at least 1.5x my own weight. I also want to do more weighted dips. I’ve always done them for higher reps, and enjoy the exercise, but I haven’t yet achieved sets of 20 with 180 lbs extra. I think it would be pretty solid if I could do that.

For legs, I’ve started doing more front squats. My squat was very hip dominant, and that’s part of why I pulled my lower back, so I’m working on making it more quad dominant.

I’d like to get it to at least 315 lbs. That would be pretty decent, especially for an upper body dominant athlete like myself. In terms of pulling, I’m taking it easy these days because of my injured bicep, but at some point, I’d like to be able to do a pull-up or a chin-up with 180 lbs.

If I was to go back in time, I don’t think I’d have much to tell my younger self. Training, just like life, is an adventure that forms us into who we are. So, I wouldn’t change anything.

But if I was able to go back in time without it messing everything up, I’d probably start training myself at three or four years old to make myself stronger. And I’d probably use my own resources to facilitate my younger self’s training so that he would have less to worry about.

🤕 How do you recover, rest and handle injuries?

Don’t try to numb it or deny it.

Everyone who trains regularly gets injured sooner or later. It’s part of the process, and it’s essential to knowing ourselves better. So, the first advice I have for you is to learn from your injuries. Learn about what you felt. Be present and aware of what’s going on in your body. Don’t try to numb it or deny it. Examine it. Understand it. That way, you may help prevent injury the next time around. Also, having a better idea of what’s going on inside of your body can help you diagnose the issue.

After that, you have to do whatever it takes to heal from your injury. Never let an injury linger. Try to allow yourself to fully heal before returning to what hurt it in the first place, whenever possible. First, you might have to rest it, taking precautions to avoid making it worse and helping your body heal. When you feel better, start using your injured body part again. Carefully ascertain what you can and cannot do. Practice what you can barely do until it no longer hurts. Then move on to something progressively harder until you regain full function.

Of course, it’s better to do that with the help of a clinician of some kind. But coming from someone who wasn’t always documented enough to have healthcare, that’s just how it works, overall. Trust me, I got injured many times. I didn’t talk about that in my story, but I broke an ankle. I broke a foot. I broke an elbow. I almost broke my back. I sprained my ankles too many times to count.

At some point when I started coaching, I injured my shoulder and couldn’t lift my arm for months. It took a year to heal from that. I tore a piece of cartilage in my wrist. It took five months for me to be able to do handstands again.

In all of those instances, caring for myself and doing everything I could to let my body heal itself did more than doctors could have done to fix me. The real problem is when your body cannot heal itself. It happens. But again, whenever possible, always, always, always allow yourself to make a full recovery.

Now, about recovery. Sleep is the most important factor. Most people don’t sleep enough. It’s too bad, because that’s when our bodies repair themselves. The more we train, the more sleep we need. Next is battling inflammation. Avoid inflammatory foods and use anti-inflammatory foods like turmeric when you cook. It can help a lot.

Similarly, avoid putting yourself in situations that could be potentially stressful for no reason. Look around you, and learn from other people’s mistakes, not just your own. That way, you can spot trouble from miles away and avoid stress.

One last thing: don’t be a one trick pony. When you get injured, adapt your training to what you can currently do, and if you have spare time, use it to develop yourself more as a human. Training is important, but other things are important, too. Try to always learn new things. Have some hobbies. That way, when you get hurt, you’ll have plenty of beneficial things to spend time on.

🍎 How is your diet and what supplements do you use?

My diet is very simple. I eat a lot of eggs and chicken, rice and potatoes, and drink 4% milk in the evening. I’m trying to eat more fruits and veggies, and am not doing too, too bad with it, but since I was a kid I always preferred foods that are high in protein.

I have always trained a lot, so I eat plenty without counting calories, but I suspect that as I age, I will start doing so, because the line between eating too much and not enough will become progressively finer as my testosterone levels lower.

I have never taken many supplements, but I experimented a bit with creatine and beta alanine last year. I didn’t feel much of a difference, but at around that time, my weight increased to 165 lbs (at 5’5”). That could be due to many factors, such as squatting daily, plus doing multiple sets of 20 twice a week, forcing myself to eat even more, and drinking more milk in order to bulk up a bit.

I stopped taking creatine and beta alanine when I stopped doing all the squats due to pulling my back and ended up cutting a bit too aggressively since I had no good reason to gain mass if I couldn’t squat much.

👍 What has inspired and motivated you?

My inspirations are pretty varied, honestly. I would say the main one is curiosity. I want to know what I can do, and I find the research process interesting, which is in big part why I tend to train on my own instead of going around trying to find a teacher.

Aside from that, like many others, Dragon Ball (a manga and anime) inspired me a lot when I was a kid. I think it might have been the most influential cultural work in the fitness industry today.

I also found the older guys in my gymnastics club very inspiring. Their skill and their toughness was something else. Seeing people better than me, or seeing people overcome adversity in badass ways also lights a fire inside of me.

But to be completely honest, inspiration and motivation tend to be temporary. What people need is a longer-term pervasive reason to do things. Inspiration and motivation can help get you excited for your training day. But solid reasons to train and desire to improve are what make you do it in the long term.

✏️ Advice for other people who want to improve themselves?

Be patient, methodical, and committed.

Start with something you are able to do almost daily, then build upon it. Identify what your goals are and formulate a logical plan to get there. Be patient, methodical, and committed. Do things for a reason. Literally every single thing you do in the gym should have a purpose.

Identify and prioritize exercises and training methods that yield a big dividend, and spend most of your time of them, because they are also probably the ones you will keep doing in the long run. It’s true for weightlifting, but also true for sports. Basics are where it’s at. Depending on what type of person you are, you might have to change everything at once, or introduce things little by little. You are the one who is best suited to determine that.

Learn as much as possible about the disciplines you are practicing, as much from personal experience as from reading, attending workshops, or getting coached by others. Have a holistic approach. Too many people’s training is fragmented and disconnected. They go to class X with coach X once a week, then class Y with coach Y twice a week, then they go do Z activity with friend Z once a week, etc.

It’s fine to do many different things, but the problem is that all of those coaches don’t communicate with each other, so you have to be the one to make sure it all fits together. Imagine doing weekly hand balancing classes with its own unique conditioning at the end, then doing Brazilian jiujitsu classes with its own conditioning at the end, then doing climbing with its own conditioning, then going to the gym. It’s a recipe for poor planning.

The more you understand training, the better you can take advantage of those classes and discuss with your various coaches how to establish a training program that makes sense while encompassing all aspects of your training.

The best hacks I have for life are not really hacks, but strategies. The idea is to cut all the things that don’t help you with your goals to a minimum so that you can reclaim your time for yourself. Time is the single most valuable thing you can ever have. You can connect the dots from there.

🤝 Are you taking on clients right now?

Yes, I am. Right now, it’s difficult to take clients in person so I’ve started taking online clients. For a long time, I didn’t really do it because training people in person is much better. But online training can still be helpful to many people, and it does have its own advantages so in the end, I was convinced enough to give it a shot.

Ideally, my clients have to be committed, and not scared of working hard. I try to go easy on them, but most people initially don’t have a very high work capacity so they still find it hard. So, the type of people I am looking for have a certain toughness or are at least committed enough that they become tougher.

Also, they need to be on top of it, message me often, and be solution oriented. A big part of coaching is solving problems over and over, and I believe that for online coaching to work, students need to be thoughtful and earnest.

My specialty is hand balancing and gymnastics strength. People tend to hire me for help in those aspects, and a recurrent theme is the need to conciliate different styles of training cohesively. I think I’m pretty good at it!

📝 Where can we learn more about you?

You can learn more about me on Instagram. I also started a YouTube channel where I make tutorials, and I have a website, which I haven’t updated in a long time, but who knows, maybe I’ll write more content eventually! I also participate on various platforms when I have the time, including Reddit.

Instagram: @jfvtraining

YouTube: wandererstraining

Website: wandererstraining.com

Forum: bodyweightlegends.com

Email: [email protected]